XVIII. Is Toxoplasma related to memory and sadomasochism? (Discreet prootion of my next book...)

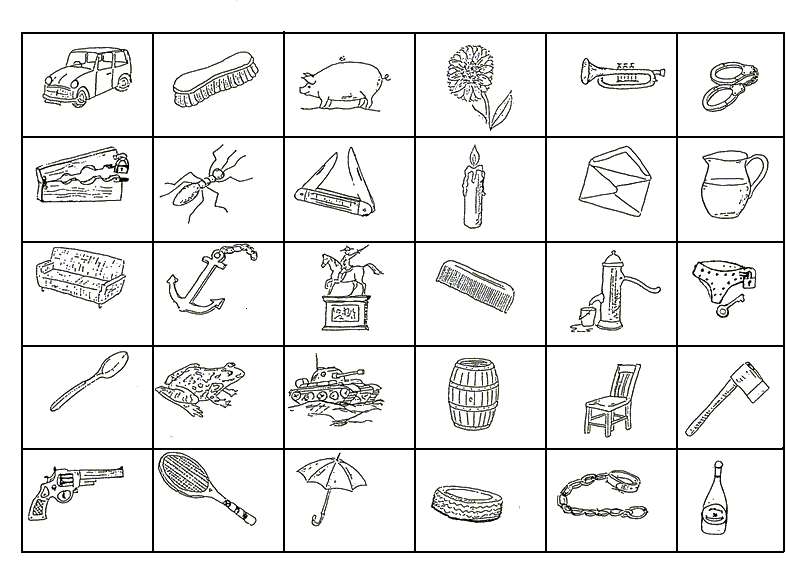

Memory does not seem to be affected by Toxoplasma – or at least not medium-term memory, which is the kind of memory we’ve mainly tested. We gave each student or soldier a piece of paper with 30 simple drawings, including pictures of a flower, water pump, chain, elephant, giraffe. The subjects had one minute to study the pictures, before they put the paper away. Then they had ninety seconds to recall the objects they had seen. (The 30 objects are shown in Fig. 42 (pg. XXx), so you can try this for yourself. But you have to do it before you continue reading, otherwise the test won’t be valid. So go on, try the test, write down the pictures you remember, and then come back to this page and continue reading

Fig. 42 You have one minute to remember as many objects from the picture as possible. Then close the book, please (don’t worry, only for short time, after while you may return to your interesting and valuable literature), and in the next 90 seconds write down all the objects you can remember. To evaluate your results see pg. XX.

The number of objects remembered by the Toxo positives versus Toxo negatives did not differ among the students nor among the soldiers. There was a certain difference in the number of incorrect answers. We still need to verify the results, but so far it seems that Toxo positives write down fewer objects that weren’t actually on the paper. However, there was a marked difference between men and women – on average, men remembered significantly fewer objects (Box 79 Do men have a worse memory than women?). Interestingly, the Rh factor also had some effect on performance: Rh negative people made more mistakes, i.e. that made up more non-existent objects.

Box 79 Do men have a worse memory than women?According to our results, yes, but that may be due to the particular test and subject group. For example, if the subjects had to memorize a path through a maze, men would probably perform better. In any case, it’s known that women perform significantly better in one type of memory test: the test of unconscious memory. We sit people in a waiting room, or have them walk through the room, and afterwards tell them to write down all the objects they remember from it. When the people know beforehand that they’ll be taking the memory test, the performance of men and women is very similar. But when they aren’t told ahead of time, the women do much better than the men. Evolutionary psychologists think that this may be related with the division of labor in our evolutionary history. If it’s true that women primarily worked at gathering, and men at hunting, then the ability to recall the location of a potentially useful plant could have been very beneficial to the women.

|

Our memory test is actually a bit more complicated than it pretends to be. We took Meili’s test of selective memory (88), and made some minor modifications, so that we could use it to measure not just memory and aggressiveness (like in the original test), but also sadomasochistic sexual preferences. At that time, I got a student who wanted to do her graduate thesis on this topic, and no other. Of course my other colleagues were reluctant to explore such sensitive ground, but I was happy to become her advisor. Maybe because I suspected that, in comparison to this topic, the other problems researched in my laboratory would finally seem completely conventional to my colleagues.

Among the thirty pictures were a couple related to aggressiveness (the revolver, knife, tank and ax), some with a sadomasochistic theme (the handcuffs, collar, chastity belt and pillory). (Well? How many of these did you remember? According to Meili, you should count only the percent of these that are found among the first ten objects on your list.) I won’t tell you what we hypothesized in the case of sadomasochism – I’m saved this intriguing topic for the next book (and believe me, dear reader, you have a lot to look forward to). But in the case of aggressiveness, we expected that the Toxo positive men would be more aggressive, meaning that they’d remember more aggressive-related objects, because they have more testosterone (Box 80 What is the relationship between testosterone and aggressiveness?)

But again nature refused to follow our expectations. We found no difference in the number of aggressive-themed objects remembered by Toxo positive or Toxo negative men or women. But it turned out that Toxo positive men remember fewer sadomasochistic objects and Toxo positive women recalled more of them. It doesn’t seem likely to me that Toxoplasma would directly affect sadomasochistic sexual preference. Rather, it’s possible that testosterone levels (which are greater in Toxo positive male students and lower in Toxo positive female students) influence sexual activity or at least sexual drive, and that sadomasochistic preference is more widespread in the population than commonly believed. Research by the famous American sexologist Alfred C. Kinsey shows that 12% of women and 22% of men are sexually aroused by a sadomasochistic story, and that 55% of women and 50% of men are aroused by a spanking from their partner. Our own results, obtained using an “internet trap” (89), were quite similar – 42%

Box 80 What is the relationship between testosterone and aggressiveness?The relationship between testosterone and aggressiveness is probably just indirect. Intraspecies aggressiveness in males is normally connected with fighting for mates. In many species, it has been observed that the victorious male experiences an increase in testosterone level, while the loser experiences a decrease. Evolutionary psychologists think that this effect exists to encourage successful males to engage in further fighting for females, while inducing unsuccessful males to avoid such fighting, and instead try to win over females in a non-violent manner. Aggressiveness, or one’s readiness and willingness to solve conflict with violence, truly correlates in males with the levels of testosterone, but the hormone itself does not induce it – testosterone only raises the male’s sexual activity. According to recent theories, a better sign of increased aggressiveness is the ratio of testosterone to cortisol. In humans, changes in testosterone – an increase for victors, a decrease for the defeated – was observed in sports games, not only among the players, but also among the fans of each team. In our students, we observed increased testosterone when they finished a written examination successfully (see Box 44 Does a student’s subconscious understand the material he’s learning better than his conscious mind?).

|

of women and 51% of men who fell into our trap chose the “gates” with a sadomasochistic theme (Box 81 How we caught sadists and masochists using an internet trap). Of course, we could think of a completely different explanation, but better to wait until we confirm the results on other subject groups.

Currently, we are attempting to verify the effect of toxoplasmosis on various types of medium-term memory, using variations on Meili’s test of selective memory. We are trying to determine whether Toxo positivity will have an effect when the test subjects don’t have to come up with the objects themselves. They will be a given a list of objects, and have to decide whether or not each object was among the pictures on the sheet. In another test, they will be instructed to click on the place where the given object was found on the previous screen.

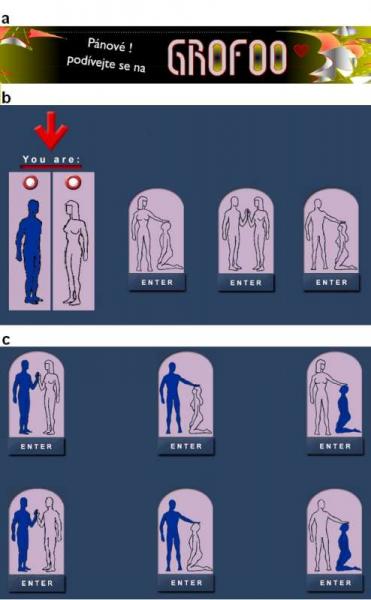

Box 81 How we caught sadists and masochists using an internetImagine that you’re on your favorite web browser, which you use to get to your email. A colorful banner ad pops up, saying “Gentlemen, come look at GROFOO!”(Fig. 43a). Or, if you registered as a woman on your email, it might say, “Ladies, look – it’s GROFOO!” instead.

Fig. 43 An internet trap to “catch” sadists and masochists. On a certain unnamed internet browser, very popular in the Czech Republic, this banner ad popped up (a). When the visitor clicked on it, he was brought to the introductory page (b), which asked him to indicate his gender. When he made his selection, the respective figure was colored in blue, and six gates appeared on the screen (c). Visitors usually persistently tried clicking on these gates, but all in vain. After clicking on any gate, they would see an hour glass appear on the screen with the message “The system is busy, please try again.” The computer counted the order, number of clicks and time between the attempts to open each gate. What do you do? Probably nothing, because one doesn’t usually click on ads without good reason. But if the ad is seen by 400,000 women and 200,000 men, then about 1,000 of these women and 800 of the men will click on it. They’ll find themselves on a homepage with three sadomasochistic pictures, and an area to indicate whether they are male or female (Fig. 43b). After selecting male or female (the icon they click is shaded in blue), they continue to another page with six gates (Fig. 43c). Now the trap awaits them: which gate will they choose? If a man chooses the gate where a blue male figure is kneeling before a not colored-in woman, the system records him as a heterosexual man with submissive (masochistic) sexual preferences. An hourglass appears on the screen, and after 5 seconds is replaced by the message “The system is busy, try a different gate.” The system notes not only which gate is chosen, but also how long the person was willing to wait – how many gates, and in what order, they attempted before leaving the trap, probably quite disgruntled. Our victims were willing to spend an average 55 seconds in the trap, and about 20% of them tried 5 or more gates (some of them repeatedly). For example, the results showed the 46% of the men preferred a woman on their level, 34% a submissive woman, 13% a dominant woman, 3% an equal man, 1.7% a submissive man and 2.5% a dominant man. For women, the results were similar: 52% preferred an equal man, 17.4% a submissive man, 18% a dominant man, 6% an equal woman, 3% a submissive woman and 3.2% a dominant woman (89).

|

The effect of latent toxoplasmosis on long-term memory was tested using two methods. First we tried to use the results of the questionnaire that we had administered earlier, when we were studying whether the psychological differences we’d determined using Cattell’s questionnaire also manifested in everyday behavior (51). Among other things, we asked the students to answer seven questions regarding rules of social etiquette, to fill out the first name of famous Czech actors and actresses, to recall how much money and how many objects they have in their wallet, and to tell us whether they remember the birthdays and name days of their friends and relatives. Toxo positive and Toxo negative people gave different answers for a number of questions. But usually a significant difference was seen in the results of Toxo positive men and women (for example, infected men remembered fewer rules of etiquette, whereas infected women remembered more in comparison to uninfected people). This shows that the differences are almost certainly due to Toxoplasma-induced psychological shifts – in this case, Superego Strength (Factor G) was lower in infected men and greater in infected women – rather than Toxo-induced changes in memory.

To further test long-term memory, we used our version of Meili’s selective memory test. Two years later, we sent the 300 students who had taken the test an email, and asked them which of the objects used in the test they could still remember. Unfortunately, two years turned out to be too long, because we got very few usable answers: the students usually apologized, that they could not remember anything. We obtained usable data from only 115 students, including 10 Toxo positive women and 9 Toxo positive men. So it’s not surprising that the results weren’t statistically significant. But the Toxo positive students who replied remembered half as many pictures and made up less than a quarter as many objects as the Toxo negatives did. Based on these results, I’d say that if Toxoplasma influences memory, then the changes are more likely related to long-term than to medium-term memory