XIX.6.6 Some pathogenic manifestations of parasitoses can effectively facilitate transmission of the parasite

Parasite disease, parasitosis, is often accompanied by a number of very serious pathogenic symptoms that frequently substantially reduce the viability of the host.At first glance, it seems that these are unspecific side manifestations of the existence and multiplication of the parasite inside the host organism or on-going defense reactions of the attacked organism.If this were true then, from an evolutionary standpoint, it would be in the interests of the parasite to reduce these manifestations to the lowest possible level.However, in actual fact, it seems that, in a great many cases, the pathogenic manifestations of parasitosis can substantially increase the probability of transmission of the parasite and thus may be elicited by a specific adaptive mechanism that has developed in the parasite during its evolution (Poulin 1994b); for a critical review see (Poulin 1995a).

A typical example could bereduction of viability, and thus also of the ability to escape from a predator amongst infected individuals of species that act as an intermediate host for a parasite transmitted from the intermediate host to the definitive host by predation – i.e. for parasites where the infected intermediate host must be caught and eaten by the definitive host (or some other intermediate host).For example, flukes of the Diplostomum genus survive in the optical lenses of fish.This, of course, reduces the eyesight of the fish and can thus affect their behavior, for example daily activity, and they stay close to the surface (Fig. XIX.18).These changes increase the chance that

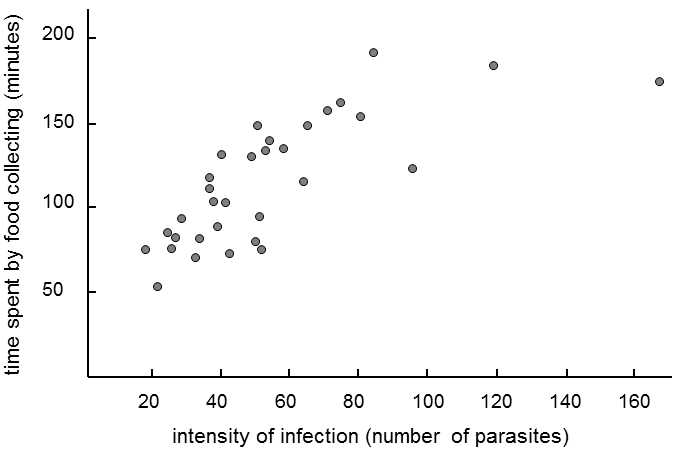

Fig. XIX.18 Dependence of the time spent collecting food on the intensity of infection. Fish with a large number of fluke worms Diplostomum spathaceum in their optical lenses spend much more time collecting food than fish infected by a low number of worms. In this case, this is primarily a consequence of the worse sight of the infected fish, rather than increased food requirements. Highly infected fish far more frequently pick up inedible objects or completely miss the collected items. Consequently, they must spend far more time collecting the same amount of food than relatively healthy fish and are thus exposed to a greater risk of predation in nature from the definitive hosts of the parasites - fish-eating birds. According to Milinski (1990).

infected individuals will be caught by the definitive host, a fish-eating bird (Brassard, Rau, & Curtis 1982).It has been demonstrated for tapeworms of the Schistocephalus genus that infected fish have greater oxygen consumption, so that they must keep to places with higher oxygen partial pressure in their natural habitats, i.e. close to the surface (Lester 1971).This again increases the probability that they will be caught by the definitive host, a fish-eating bird.

Leishmaniaprotozoa, close relatives of Trypanosoma – thecausal agent of sleeping sickness, mechanically block or enzymatically damage some parts of the digestive tube of their insect vector, so that parasitized sandflies (Phlebotomus) are capable of penetrating the skin of the host and thus of infecting it, but not of sucking blood (Schlein 1993).Thus, infected individuals with blocked suction organs repeatedly attempt to withdraw blood from various individuals and consequently infect more hosts.The causal agent of plague, Yersinia pestis bacteria transmitted by fleas, apparently increases the effectiveness of their transmission in a similar way (Voronova 1989).

Parasitic protozoa of the Plasmodium genus, the causal agent of malaria, cause a sharp increase in body temperature in the host organism.This process, similar to a number of intense processes connected with immune reactions, is extremely energy-demanding and exhausting for the host This reduces both the ability of immune defense of the host against the parasite in the blood and also its ability of avoid attack by the vector, mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus (Barnard & Behnke 1990).It has even been observed that infected mice expose themselves most to attacks by mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus exactly at the time of the greatest occurrence of gametocytes of the parasitic protozoa Plasmodium in their blood (Day & Edman 1983).Anorexia caused, for example, by some parasitic helminths, could have a similar function (reducing the functioning of the immune system) (Hall 1985).

It is very difficult to recognize manipulative activity of a parasite mediated by unspecific pathological symptoms.In most cases, it is very hard to decide whether a certain pathological manifestation of parasitosis developed like any other adaptive trait facilitating easier transmission of the parasite or whether this is a side effect of the disease that is basically undesirable from the viewpoint of the parasite.The only guideline could be exact quantitative evaluation of the effect of the given pathological symptom on the effectiveness of transmission of the parasite.If a certain pathological symptom reduces the viability of the host and simultaneously does not contribute to transmission of the parasite, then it is in the interests of both the parasite and the host to develop a mechanism to reduce this symptom.Experience with some helminthoses indicates that such mechanisms could actually have evolved in evolution and that pathological symptoms need not necessarily be accompanied by massive parasitosis.Large ascites are formed in mice infected by the tapeworm Taenia crassiceps – accumulation of up to several milliliters of liquid in the stomach cavity, containing large numbers of parasites.Simultaneously, it seems that the mouse is in no way handicapped by the existence of the parasite; at least in ethological experiments, it behaves in exactly the same way as a healthy mouse.If a specialized parasite that is long-term adapted to a certain host species causes marked pathogenic symptoms in its natural (but not unnatural) host and these symptoms simultaneously increase the effectiveness of its transmission, then it seems highly probable that this is a manifestation of manipulative activity of the parasite.