XVII.1.4 It is sometimes difficult to draw a clear line between inborn and acquired traits

To a first approximation, it might seem that there is a sharp borderline between inborn traits and those acquired by cultural transmission.In actual fact, this is frequently not true.This is a result of the fact that genes do not directly encode the existence of a certain trait, for example certain morphological structures or patterns of behavior, but rather program or, to be more exact, affect the progress of epigenetic processes, which only then create the relevant trait during ontogenesis (see XII.7).The progress of these epigenetic processes is simultaneously affected by and sometimes even dependent on the specific effects of the external environment, including the social environment (Gottlieb 1998; Jablonka, Lamb, & Avital 1998; Van Speybroeck 2000).The occurrence or absence of a certain pattern of behavior can thus be connected with the genetically determined level of a neuromodulator (e.g. dopamine), which affects the degree to which the individual searches for new stimuli (Cloninger, Svrakic, & Przybeck 1993), and thus the probability with which it will encounter a certain external stimulus inducing the emergence of the relevant behavior.On the other hand, a certain external stimulus, for example the way that its parents treat an offspring, can very strongly and for a long time affect the levels of neuromodulators and thus the way in which the particular individual will react to certain external or even internal (genetically determined) stimuli – whether these external stimuli lead to or do not lead to the emergence of certain behavior.The levels of neuromodulators can also directly affect which genes will be expressed by the particular organism and thus which genetically determined traits will occur in the particular individual (Gottlieb 1998).As the way in which parents treat their young can also affect the future parental behavior of these offspring, the relevant patterns of parental behavior can be transmitted epigenetically from generation to generation similarly as genes are transmitted from one generation to the next (Francis et al. 1999)(Fig. XVII.4).

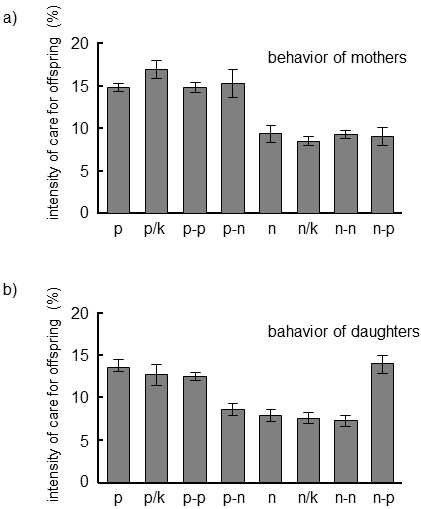

Fig. XVII.4 Vertical nongenetical transmission of a trait. On the basis of observations performed over 10 days from the birth of the offspring, female laboratory rats were divided into two categories: into the category of caring mothers, i.e. mothers that frequently licked and cleaned their offspring during feeding (p) and the category of mothers that did not pay much attention to their young (n). On the basis of experiments with transfer of offspring between nests, a study was made in the following two generations of how this behavioral trait is inherited. It was observed in the first generation that the daughters of caring mothers very frequently licked their offspring, both under natural conditions (p) and also when 2 offspring were removed from the nest and then returned to the same nest after 15 minutes (p/k) and when 2 offspring of other caring mothers were put in their nests (p-p) or two offspring of uncaring mothers (p-n). To the contrary, the daughters of uncaring mothers cared less for their offspring, both under natural conditions (n) and also when 2 offspring were removed from the nest and then returned to the same nest after 15 minutes (n/k) and when 2 offspring of other uncaring mothers were put in their nests (n-n) or two offspring of caring mothers (n-p). The maternal behavior of the biological and adoptive daughters was then studied in the following generation. In this generation, the offspring were not moved between nests, so that the descriptions in the individual columns correspond to the nest from which the mother came. It is apparent from graph (b) that the intensity of care for offspring is not inherited from the biological mother, but always from the adoptive mother (step-mother). The heights of the columns correspond to the average frequency of caring for offspring and the error bars depict the mean error in the average. According to Francis et al. (1999).